•

December 5, 2024

Chloe Duckworth’s Interview:

Interview questions and transcript:

Chloe Duckworth’s an entrepreneur within the neurotech space. She graduated from the University of Southern California with her bachelor's degree in computational neuroscience. Since 2022, she's been the Co founder of and CEO of Valence Vibrations. So this is a neurotech company that focuses on emotional analysis using AI on data taken from conversations in person and online as well. Chloe Duckworth technology allows individuals to gain insights into how users, customers and Co workers respond using AI. This is very crucial as this bridges the gap in communication across people's screens and languages.

Chloe’s backstory

{ 4:15 }

Let me just briefly introduce myself as well. So a couple of years ago, I was in your shoes literally, but I was at USC, so similar seats and was starting my college journey in neurotech. Was quite interested in trying to explore the tech side then going into pre Med which is what I had originally started as and my first opportunity started because of the pandemic. I was able toable to intern with brain minds and learn a lot about brain computer interfaces and opportunities within neurotech neuro ethics and that really catalyzed my ability to start a company while I was in school.

Started Valence as an emotion AI company was really more of just a side project. Honestly. I was the COVID generation of students like many of you probably that had my college experience curtailed by the pandemic. I was a freshman, so I basically was at school for six months at USC and then they shut everything down. We came home, attended all of our classes on Zoom, like many of you probably attended high school, and I started working on start-ups during that time and I learned a lot throughout that process. I think I truly wouldn't have been able to start the company that I built if the pandemic hadn't happened. I was basically taking my tests on the weekends, I was watching lectures at night and then working full time on the start up since I was 19. I'm 23 now. So it's been a bit of a journey.

{ 5:51 }

And then ended up graduating USC a couple years early when we raised money and our investors said you either have to drop out or graduate early and go full time on the start up. So it's been quite a journey, but I'm excited to be here today and talk to you all about opportunities within entrepreneurship and neuroscience and ways to break into the field. I am really passionate about that and would love to learn more about some of your sort of pathways into studying neuroscience as well. So to have a, a Long story short in answering your question, the more mission of Valence and really the, the technology that we're building is to better connect people. So I'm sitting here about 350 miles away from all of you in San Francisco. I have a bunch of customer meetings this week, so I couldn't be there in person. But we're able to connect across these screens, understand each other, and with Valence, we're able to add that emotional layer back into the conversation.

{ 6:52 }

So we work with a lot of contact centers, some video conferencing platforms that you'll be seeing very shortly, one of whom you are currently using. So really excited to be able to bridge emotional barriers across people with different neurotypes like autism and ADHD, accents, age, gender differences, locational differences across the country with a lot of different dialects and how you speak English. And really the goal of our technology is to help connect people across different emotional communication styles to better understand each other in digital spaces. And that's been the core mission since being a consumer neurodiversity app on the Apple Watch to today selling enterprise voice AI tech.

How did the idea of Valence vibrations come about?

{ 7:49 }

Essentially Shannon, my Co founder and myself met at USC.

We lived right across from each other in the forum and bonded over a love of AI neuroscience. You can see from my background, I studied economics and was working for the Human Connectome project for a while and was really interested in how we can model neurological processes using AI. At the time I was interested in this idea of neuromorphic computing. I'm sure some of you are familiar with it, essentially being able to model artificial neural networks structurally and functionally like a neural network in the brain. And neuromorphic computing sort of fell out of favour since then. But, and I think that there's a lot of good reasons for that, like artificial intelligence isn't live wired in the same way that our synapses grow and change in response to new information.

And so the actual structure of what an artificial neural network looks like is quite different, but the function of being able to learn patterns with new information and grow over time and have positive and negative feedback loops is quite similar. And so I was really interested in that intersection, and was able to start working on a couple of different side projects at my first startup, which was actually called Brain Strong. We built a reminiscence therapy app for dementia, helping people with mild cognitive impairment sort of stave off the impacts of that impairment before it led to dementia. With what's called reminiscence therapy, where you're essentially being quizzed and reminded of your past life when you got married. The children that you had a lot of your earliest memories of are the last to go and are quizzed daily like a Duolingo, but on your own life and your own memory.

And then also tracking your activities of daily living, your sort of impairment over time and essentially tracking the delay in the mild cognitive impairment sort of advancement through this application ended up growing that starting when I was 18, you're going to get acquired by this dementia caregiver company. I won't say the name, but they ended up pulling out of the deal in a very unethical way because we didn't have the right legal paperwork in play to really protect us and protect our IP. And we were 18, and didn't know what we were doing. So that acquisition fell through. We lost all of our IP for that company. And that was my first, first big failure at USC and, and as a founder. But what I learned from that and when I brought 2 Valens, when we started entering hackathons in Neurotech to improve emotional communication and originally for just autistic people on an Apple Watch. And we learned all those IP lessons from the previous startup and brought that to where we are today. So now we have a team of like 10 lawyers and it's very expensive and it's totally worth it and won't make the same mistakes again.

When it comes to challenges within your company when handling users, how exactly do you address potential ethics and privacy concerns?

{ 11:13 }

Totally. So I think AI ethics, AI privacy, and you probably have also heard the term AI safety, These are all really important concepts. These are more theoretical value based judgments when we think about ethics, what is right, what is the proper way to ensure that our users are getting value from our product without being exploited. And there's also legal frameworks surrounding compliance, provenance, governance, and these become very hairy issues when you're adding that layer of compliance. So I'll sort of break this question down.

{ 11:55 }

When we think about data privacy, we have a whole page on our website called our Our Ethics and Our Values where we talk about we believe that our technology should be used as an extension of friendship and connection. We want users to be choosers. That's sort of our slogan. Like, we want people to be able to decide what happens with their data, how it's used, take in a minimum necessary amount of data to be able to output something of value to users that they are paying for, but not invade their privacy. And I think, you know, often times neuroethicists refer to the brain as like the last frontier of human privacy. And I tend to agree. I think our entire lives from our geolocation to all sorts of sensitive matters of identity, of values, of politics and religion, all this data is being tracked with a persistent user identifier across the Internet. And this is not to get, you know, my tinfoil hat on.

{ 12:57 }

This is something that is happening all across the country and across the globe. Certain areas like the EU are better with things like GDPR where they have more data privacy protections. But truly, it's very difficult. And I think we need to protect the sovereignty of our thoughts, of our memories, of our joys and our sorrows in our brain. And so the way that we think about data is what is the minimum necessary amount of data that we need to accomplish what people are paying us for, the value that our product delivers? What do we need to be able to reach people in marketing but enable them to opt in to data that doesn't necessarily need to be taken in? A great example would be that we can fine tune models to optimize for particular types of accents, particular context of conversations that are happening in one workplace versus a call centre, but we don't have to. We can give someone a baseline model.

{ 13:57 }

We don't have to record or save any data we have on Prem or edge applications that are running locally on someone's device where we never see any of your audio data or the emotion output from that audio data. It's that's really the way that we think about sort of the standards of data privacy. And then on top of that we have to meet certain legal requirements like GDPR in the EU, like the EUAI Act that does classify certain types of emotion recognition as high risk systems. So there's added compliance measures and really a lot of expense that goes into being compliant with things like that. And in the United States, there's also a number of regulations. The standard one within enterprise companies is called SoC 2 compliance. It often takes six months and hundreds of thousands of dollars. So data privacy, security and ethics are really important and it's important to take, in my opinion, strong stances on these issues.

{ 14:57 }

But then there's also this added layer of being able to prove repeatedly that you are following those standards and that's through these audits and the compliance measures.

What exactly is the product that you are providing with Valence vibrations?

{ 15:42 }

Sure, I'd love to show you actually. I know that maybe the folks on the podcast won't be able to see it, but we'd love to show you in the room what this looks like.

{ 15:50 }

So a perfect example would be McDonald's recently automated all of their AI voices or their kiosks to include AI voices. So when you drive through a McDonald's, there's an IBM voice that's speaking to you, saying what would you like to order? You order a Big Mac and it takes your order. Now McDonald's recently cancelled their contract with IBM because these AI voices didn't have a motion context. Great example. Someone comes in the middle of the night, they're drunk, Hopefully they're not the one driving, but they're pulling through the drive thru. Maybe they're in the passenger seat and they say, shit, I love a Big Mac. Now the large language model behind that kiosk is responding to a curse word saying this customer is angry at us. Now we can't take the rest of this order. We're going to escalate this to a human. Now that customer wasn't angry. That order didn't need to be escalated to a human. McDonald's has spent millions of dollars on their AI voices that have no emotional intelligence.

{ 16:59 }

Humans are also working the same shift, so they're double paying this AI technology plus a human to answer this order. What we do as a company is essentially provide the emotional intelligence layer to conversational engines, whether that be human to human conversations in a contact center on Zoom in the sales context, or an AI voice speaking to a human when you're ordering a McDonald's or when you're calling the robo caller for your doctor's office to make an appointment. We're adding emotional intelligence to these systems so that you can get through conversations more efficiently and effectively online and get less frustrated. We started, and I previously mentioned launching a consumer application, but should have gone into detail. We initially launched an app called Vibes. It's still in the App Store. And essentially this was a sensory substitution technology that I originally created because my mentor, David Eagleman was big in sensory substitution with his company Neo Sensory.

{ 18:00 }

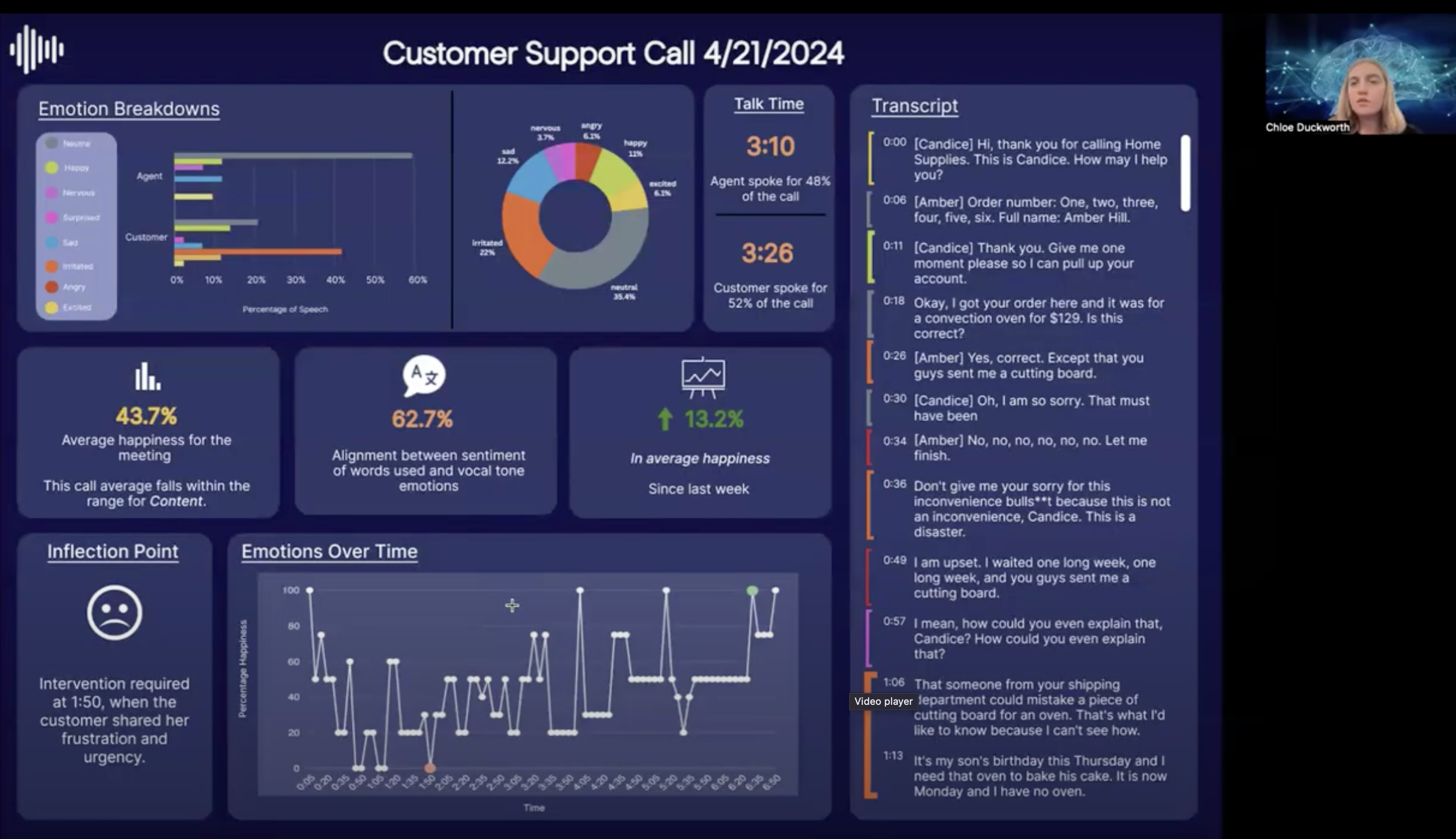

And they help deaf and hard of hearing people interpret sound as vibration. And so we came up with this idea of augmenting emotional communication as like a tangible signal on a wearable. So you can literally feel the vibes of the room as a vibration on your wrist on the Apple Watch app. So that was our first product and now we launched Enterprise APIs and other products that are essentially doing the same thing, but at a much larger scale of how we can look at tone and tonal inflections over time across many different voices and analyze the emotions in them. And I will share my screen very, very briefly just so you can see what that looks like in a contact center. So essentially we're looking at the breakdown of emotions throughout a conversation as someone gets pissed off, as someone is frustrated.

{ 18:53 }

There's opportunities to turn the conversation around, make it go smoother, reduce miscommunications and sales conversations. There's also opportunities for upsell. When a customer's happy or they feel satisfied with your service, you can sell them something else. You can get what they call NPS Net Promoter Score. That's the score that companies use to decide whether or not they're effectively marketing something. We can track how happy a customer is throughout the entire life cycle of that relationship.

How exactly did you get your data set? Where did you get it from? And how exactly did you incorporate all these different tones into your model?

{ 19:51 }

So I think early on when we were looking at the competitive markets, skip, what we learned is that most companies aren't truly representative in their diversity statistics that they're training models on. What I mean by that is, they'll hit baseline demographic populations of, say, having 13% Black voices in our data set for North American English speakers. But they don't hit the level of intersectionality when it comes to race, gender, age, neurotype like autism and ADHD, which does affect your tonal expression, etcetera. So what we did is we crowd sourced data from the exact population proportions of each of these groups and also how they overlap with each other. And we trained models based off of these crowd sourced data sets. We asked people to respond to an emotional situation as they would as if it was happening to them. And we recorded hundreds of thousands of data samples that way.

{ 20:55 }

And then after that we partnered with this lab called Stanford Research Institute, their speech lab. The star lab invented Siri prior to Siri getting acquired by Apple for a billion dollars. And I was friends and had met some of the Siri Co founders ahead of time and they connected me with Sri. And so then we got access to a lot of that early data as well. So we trained our models based off of our crowd sourced data. It's all self annotated. When people said I am feeling happy in this moment, and then also the Sri data that was also self annotated. Just to take a quick second. The reason why I say self annotated and why that's important to mention is because a lot of data that you're seeing in our training models is literally someone else from another country. Oftentimes sitting there manually annotating data as happy, sad, angry, in a different language in a different accent with absolutely no context on how that person was actually feeling.

{ 21:57 }

So that's the baseline for our market right now and why the other emotion AI models just aren't performing very well because they didn't ask people how they were feeling and record it. They recorded actors' feelings however they were feeling, then annotated that data after the fact by someone that was completely different from them. And we found that emotional perception is highest when you're speaking to someone of your own age, race, gender, neurotype, etcetera. I'm sure some of you have seen those studies where they say that white people have the lowest emotional perception and empathy scores of any race or any people of color in pain. And they've shown white people versus Asian people versus black people photos of different races experiencing pain. And white people are by far the worst at identifying and empathizing with pain in people of color. And what we've taken from that is a couple of things.

{ 22:54 }

Now, that certainly has implications for white supremacy, but I think on a more fundamental level, the ability to recognize emotions is essential for empathy. And when you are part of a dominant group or an in Group, your ability to perceive the emotions of people that you consider other or outside of the group that you grew up with significantly decreases. So when we look at workplace culture, when we look at toxicity, racism, all sorts of HR violations that are happening when people are experiencing digital workplace, digital conversations, a lot of this is actually because we just don't understand each other. We come from different backgrounds and that's part of what makes communication so unique and so beautiful that we get to be able to experience different types of people. But when you are part of an in Group, your ability to perceive the emotions and and vibe check someone outside of your group significantly diminishes.

{ 23:54 }

And so using technology like ours, we're able to really level the playing field and help people feel more empowered, comfortable, and understood with equal understanding of emotions across different types of people. And with a model like ours, we're able to train it off of hundreds of thousands, millions of people. So we're able to empower all of those marginalized voices to feel understood by our model in a way that a human brain could never experience that many people in a lifetime and learn to understand their very nuanced patterns in tone. So that's the way that we think about building representative models.

How did you secure funding for your company and what advice would you give to young entrepreneurs who would like to go down that route?

{ 24:51 }

Yeah, so we started to call the family and friends rounds. Now everyone has different family and friends.

{ 24:59 }

Personally, at the time, I didn't have the type of family and friends that were like cutting out 500K checks, like Willy nilly. Like, you know, I couldn't go to my parents and ask them for $1,000,000. Like some of the other founders that have made it. I think Jeff Bezos got like 300K from his parents. Donald Trump famously got a small loan of $1,000,000 from his dad. I do have some family and friends support, and that's kind of your first round, oftentimes prior to raising any money. It's called bootstrapping, where you're essentially just making it with your savings and not raising any outside capital. And then your first investors are called Angel investors where they give you between 5000 and $50,000 and they're people you know, or other people that work in tech that really believe in you and believe in your company and they get equity in return for their investments.

{ 25:59 }

And then there's venture capitalists, which are like the the big funds that invest in early and late stage founders. And that's more of like a formalized process. So when I first started out, I asked family and friends, raised a little bit of money that way. And then once we were able to sort of prove a little bit more, build a prototype, we were able to raise money from some Angel investors that we didn't know, but we're able to like network to, to get in touch with through USC and some of the programs that we joined there, as well as just a ton of LinkedIn cold outreach. I, I say it in literally every talk that I give, and I'm going to say it again. You were literally 1 cold email away from changing your life. My cold email that first changed my life was a celebrity neuroscientist, David Eagleman, responding to meet me when I was a freshman in college and so impressed by his career. He's one of the top neuroscientists in the country, if not the world right now.

{ 27:00 }

And he responded to my email with interest in learning about me and being able to help support my success. And because of that, I entered his sakathon and started his company and became a founder at 19. So cold emails go a long way. Eventually raise the PRECEDE rounds. And there's a more formalized process for that, which I'm happy to share. But a lot of it was networking into the right relationships that I didn't already have. And like I spent years building my network. Or sometimes it's not the first person you reach out to with their friend or their friend's friend or their friend's friend ad nauseam. I think our first big investor that gave us 500K was like a friend of a friend of a friend through all these sporadic LinkedIn networking calls that I took.

{ 27:47 }

So my best advice is when you're at this stage in life and you're just figuring it out, spend a lot of time networking with people that you're interested in their career, people that you don't know much about what they do, but you're you're quite interested to learn. And even for people that it wasn't like an immediately valuable conversation, I didn't necessarily walk out of there wanting their career. Oftentimes it came around later on where they had some tangential connection to someone that I wanted to meet. And because they had met me before, they were able to introduce me. So really like the best advice is you're in a competitive space. It's really tough for young people to get involved in neurotech. It's a very competitive, difficult profession to get in without a PhD. I'm sure a lot of you are on free Med or PhD paths or MDPHD, but if you're not and you want to like jump into the industry right out of college, best advices to network because these are not types of jobs that you can just like click apply, mass apply on indeed or LinkedIn. Like I've never gotten an opportunity that way. None of my friends that I know that are successful right now got their job from applying on LinkedIn or indeed.

{ 28:58 }

That's kind of the best way to have your resume not really be looked at at the bottom of the stack, at least in this profession. Even when we're hiring interns, like every year we hire interns, we get like 500 applications in the first week. And like we're sifting through a ton of people that all have very similar backgrounds. The people that we pick inevitably are the people that reach out with a ton of initiative. I can tell you, like the previous founder of your club, Souli of CruX, he reached out to me. He's my intern for six months and then he started the BCI conference every year and he had an excellent, cool message to me and that's how he got his opportunity and now he's running his own startup. So that's my best advice.

How do you see neurotechnology rapidly advancing and what do you think are the best opportunities within the space?

{ 30:01 }

So I think for the last really 2 decades to, to some extent, we have seen a renaissance of hardware, of material science, of these sort of hard sciences where people are really trying to figure out like how can we get biocompatible materials to implants in the brain or even like the right electrode configuration for like wet or dry EEG caps non invasively. Now, there are some minimally invasive techniques that also came about in the last couple of years, like ultrasounds where you're simulating based off of Sonic waves and you don't need to have any sort of craniotomy. I see that because I think that there is still so much that we need to learn from the material science aspect of biocompatibility, of stability within the brain of signal to noise ratio.

{ 30:57 }

But I think that right now we're really seeing an interesting time where software is going to flourish. Now we're finally getting somewhere with a signal to noise ratio. Neuralink is in later stage trials, Paradromics, Synchron, these companies that you might not know the names of, but they're actually way further along the neural link and just don't get all the press because they don't have Elon Musk's name attached. They're getting real data from these implanted arrays. We need software and we need AI to be able to interpret this data. I think we have access to 10 years of data for some patients, but over time, you need to consistently recalibrate the tools that you're using. But then we also need to optimize machine learning to decode all these, like very noisy signals, especially as they degrade over time. And I haven't seen the field really flourish in software in the way that I think that it should be.

{ 31:57 }

I think that's going to be a pivotal moment in the next 5 years. And I'm sure a lot of the people sitting in this room don't want to wait to get a PhD to work in neurotech. My advice for you is really go strong on software and AI and hit the ground early as being kind of that Swiss Army knife that has the material science background from computational neuroscience that understands biologically how these systems work, but also has a software background to really add value at decoding the signals. Because neuroscientists typically don't have that background and electrical engineers oftentimes don't have a really sturdy background In machine learning, though, it's becoming more a part of the curriculum in the last couple of years I've noticed. So that is my advice for folks that are wanting to enter neurotech, especially like the Med tech elements of neurotech.

How long did you bootstrap for and when did you know when it is enough you move on?

{ 33:12 }

You don't really know until someone gives you a check. Like there's not like a fast and easy answer. Unfortunately. I've known some people that like to join my accommodator, which is a big accelerator where you can get investment. It's more high profile, but it's more competitive to get into Harvard and you can quit your job or drop out of school immediately and be in a decent space where you don't need to be bootstrapped that long. I've bootstrapped for about a year before raising any outside capital. During that time we did raise some money from family and friends to kind of keep us afloat and funds like early prototypes.

{ 33:48 }

But I would say the faster you can get to building something that sucks, but you can tangibly see and demo and show people that's the best way to do it. Back in 2021 and, and, and prior to that, there was basically a 0 interest rate environment for those that don't have an economics background. What that means is that because interest rates were so low, the cost of capital was really low. They were able to invest in often shitty ideas with very little risk because it was a low interest rate environment. Now, I mean, thankfully, Jerome Powell at the Fed dropped rates recently, but interest rates have been really high for the last two years. And so it was much harder to raise capital because investors really cared about business fundamentals and were less likely to like, take kind of a risk on a new idea from students that were just starting out and hadn't built anything and it was just an idea in your head then they were a couple of years ago. I say that markets change constantly.

{ 34:57 }

If you have a good idea and you want to take the leap, do it, but be warned that raising capital is really difficult. I usually advise people like if you can and if you're in a position where you already have a job, save up a year of salary before you decide to quit that job. Like having some savings to bank on because you can't bank on raising capital immediately. I think the lowest risk time to raise capital is when you're still in school because you're still hopefully passing your classes like I was, but you're able to dedicate time into the startup to really see the idea along. It's slower than if you're working on it full time, but you still have the financial ability oftentimes to not have to work another full time job if you're being supported in college through aid or through parents. And so it's, it's less risky often to try to start a company in college. Then later on in life where you might have a family and kids and people will depend on you and you might have a high paying job that's really hard to quit.

Why did you make that shift towards emotional intelligence?

We essentially started the consumer neurodiversity app. We started wanting to save the world. We were like naive college students that truly wanted to just make communication easier for neurodivergent people. We were in the neurodiversity team. This is something we really cared about. I grew up struggling with emotional perception, feeling like there was subtext that I missed, you know, struggling to fit in socially because of that. I didn't have like a diagnosis or a reason why necessarily at the time, but we wanted to create technology to improve emotional connection across people with different sensory processing systems and to empower neuro diversity without stigmatizing it and without this presupposition that autism is a disorder, a disease needs to be treated or cured, but rather a neurotype or sensory processing system that needs to be supported and understood in a different way.

{ 38:00 }

And that's sort of the concept of universal design. Like how can we create technology that is truly as accessible and inclusive for everyone that makes the experience better for everyone? It's like, I'm not deaf, but I love using subtitles on Netflix because it just helps me fill in the blanks sometimes. Sometimes you're eating something that's crunchy and you can't hear over the noise of the TV so you can see the subtitles. That's the concept of universal design. So we were really interested in that mission, learned a lot testing it in the market, grew it to 20,000 users, but struggled with monetization because autistic adults from the United States are either 80% unemployed or underemployed. So trying to sell an expensive application for an Apple Watch, which is already expensive, was just not going to be a feasible business model and also not going to impact the people that we really wanted to help.

{ 38:54 }

And so instead, we pivoted into enterprise AI so that we could impact people in a much more exponential scale, but also meet them where they were at in the platforms you're already using, like Zoom and Teams. Rather than unintentionally stigmatizing people by forcing them to use this kind of like niche platform on an Apple Watch that a lot of people didn't have access to and it wasn't necessarily meeting them when they were already having conversations in the workplace.