•

April 1, 2025

Have you ever taken a personality test and shared the results with friends? Or perhaps been asked personality assessments from employers? Whether it’s the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Enneagram, or the DISC assessment, personality tests have become a global obsession. We love categorizing ourselves and others into neat little boxes—introvert or extrovert, thinker or feeler, task-oriented or people-oriented. Personality tests offer a sense of identity and clarity in a chaotic world. They help us make sense of our behaviors, preferences, and relationships when venturing through unknown possibilities. For many, these tests are more than just fun— whether for bonding over shared personality types or using the results to improve communication in relationships, they’re a way to connect with others.

Among all trends, one zooms in on how we express and receive love: the Five Love Languages. Introduced by psychologist Gary Chapman in his 1992 book, this concept has evolved into a cultural phenomenon. According to the 5 Love Languages’ official website, over 50 million people have completed the assessment to find out how to strengthen their relationships. The concept has permeated popular culture to such an extent that even dating applications like Tinder have incorporated similar "love style" features.

For those unfamiliar, Chapman categorizes the ways people express and experience love into five types:

Physical Touch: Expressing love through hugs, kisses, or holding hands.

Receiving/Giving Gifts: Feeling loved when receiving thoughtful presents or giving them to others.

Words of Affirmation: Valuing verbal expressions of love, such as compliments or encouragement.

Acts of Service: Feeling cared for when someone does something helpful, like cooking a meal or running an errand.

Quality Time: Prioritizing undivided attention and meaningful moments together.

(from simplypsychology.org)

However, these concepts are commonly questioned: is the Five Love Languages theory grounded in science, or is it just another way to get stuck in stereotypes? While the Five Love Languages theory lacks rigorous scientific validation, its principles do align with some established findings in neuroscience and psychology.

Physical touch, such as hugging or holding hands, triggers the release of oxytocin, the “love hormone.” This neurochemical enhances feelings of intimacy and trust, promotes prosocial behaviors, and reduces levels of cortisol, a stress hormone. Research has shown that more frequent hugging behavior between partners is linked to lower blood pressure, heart rate (Light et al., 2004), and cardiovascular reactivity (Grewen et al., 2003).

The significance of physical touch extends beyond romantic relationships and can be understood through psychological and cultural lenses. According to attachment theory, early physical touch—such as an infant being held by their mother—fundamentally shapes adult relationship patterns. Harry Harlow's landmark monkey experiments reinforce this concept, showing that infant monkeys preferred comfort from a soft cloth surrogate over a wire one that provided food (Harlow, 1958).

(Harlow’s Cloth Mother Surrogate with Infant Monkey^3)

Adult attachment styles also significantly influence touch satisfaction in relationships. Those with higher attachment anxiety may desire more physical touch but struggle with satisfaction due to insecurities. In contrast, individuals with avoidant attachment styles often prefer less physical contact (Takano & Mogi, 2019). Touch satisfaction is positively linked to marital quality, and early experiences of physical affection in childhood can shape healthier adult relationships.

Cultural attitudes toward physical touch vary widely. In some cultures, public displays of affection, such as holding hands or kissing, are commonplace and socially accepted, while in others, such behaviors may be considered inappropriate. These cultural differences underscore the importance of finding a partner who respects and matches your level of comfort with physical touch.

For the second love language, receiving gifts, we can split the case into giving gifts and receiving them. While the direct neurological evidence linking gift-receiving to improved relationship satisfaction is limited, insights into the brain’s dopamine reward system offer an understanding of its potential impact. When we receive an unexpected gift, our brain's pleasure center (nucleus accumbens) activates, releasing dopamine and creating a sense of joy. This "emotional intensification" explains why surprise gifts often feel more special than expected ones.

Gift-giving has stronger scientific support. Studies show that giving gifts activates brain regions linked to prosocial behavior and emotional bonding, such as the prefrontal cortex. The act of giving also triggers oxytocin release, deepening connections. Research published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that practical, easily obtainable gifts were more effective at reducing psychological distance compared to aspirational, higher-value presents (Rim et al., 2018). The similarity in gift preferences between partners is linked to higher relationship quality.

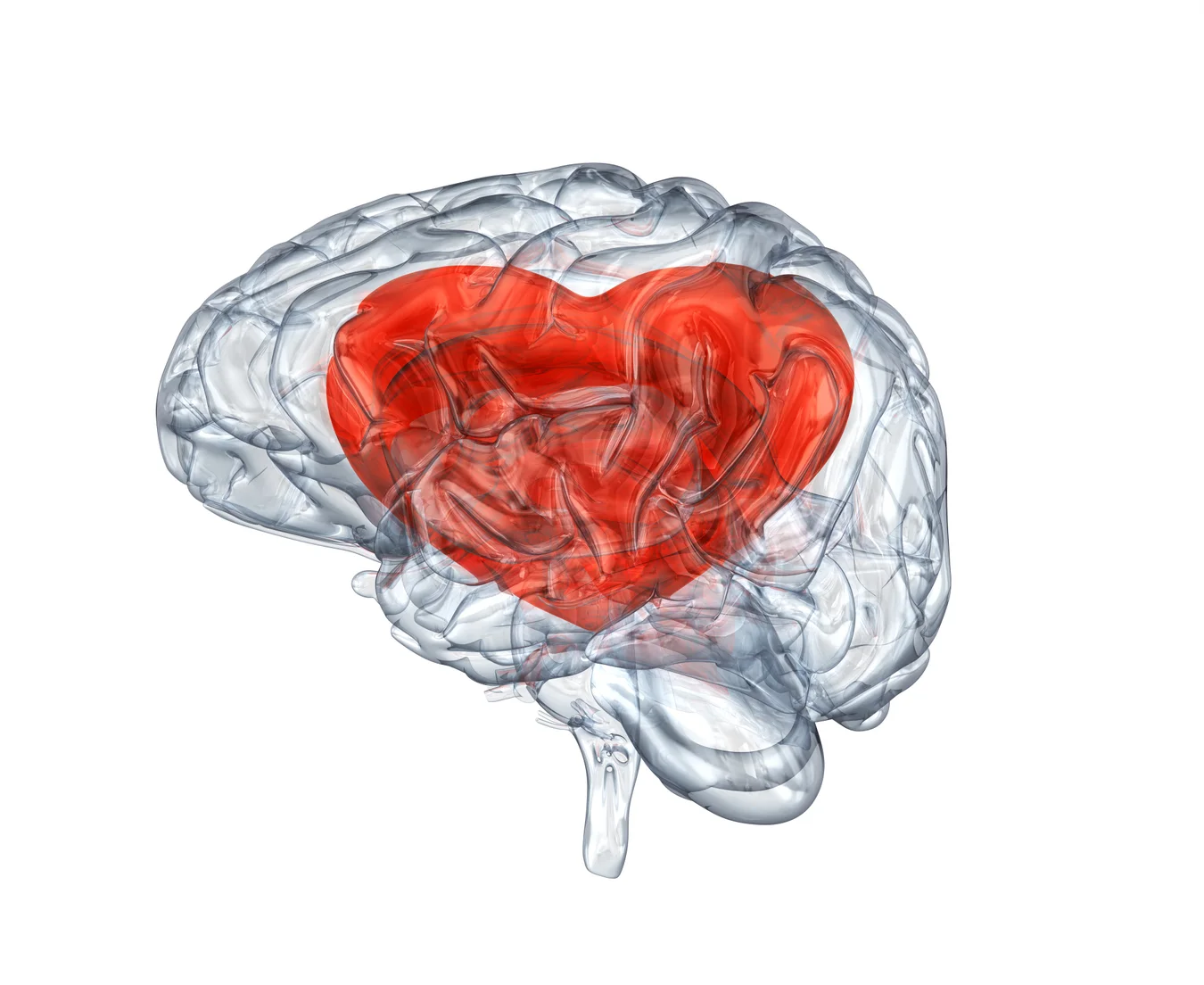

Another group of researchers investigated the impact of gift exchange between friends on cooperative selective attention tasks. They investigated how gift exchange between friends affects cognitive performance during cooperative tasks. Results showed improved performance, with participants demonstrating higher accuracy and faster response times (Balconi et al., 2019). A third study, published in PubMed Central, explained the previous observation by using Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) in hyperscanning. Following gift exchange, researchers noticed enhanced brain connectivity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, associated with improved cognitive performance and stronger interpersonal bonds (Balconi & Fronda, 2020).

(Participants conducted gift giving and receiving before the third pair of scanning, the red area represents the increase in intra-brain connectivity^7 )

However, the effectiveness of gift-giving in relationships is not universal. Repeated mismatches in gifting can highlight deeper incompatibilities, potentially affecting long-term relationship stability. Additionally, attachment style plays a crucial role in how gifts are perceived. A study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology found that individuals with avoidant attachment styles were more likely to perceive gifts as being given out of obligation rather than genuine willingness, potentially as a defense mechanism against increasing intimacy (Beck & Clark, 2010). On the other hand, securely attached individuals tend to see gifts as natural expressions of love, focusing on thoughtfulness rather than material value. In contrast, anxiously attached individuals often view gifts as a measure of love or commitment, which can lead to heightened expectations and potential disappointment. This suggests that the effectiveness of gift-giving as a love language may vary depending on individual attachment styles and relationship contexts.

Acts of service, though less extensively studied than other love languages, likely share similar psychological and neurological mechanisms with gift exchange. When a partner fulfills a need—such as completing a household task or running an errand—this could activate the brain's dopamine reward system, creating appreciation and joy. Similarly, helping a partner may trigger oxytocin release, fostering generosity and emotional bonding.

The limited research on acts of service makes any definitive conclusions difficult. Future studies could explore how these actions influence relationship satisfaction and whether they engage the brain's reward and bonding systems similarly to gift-giving or physical touch.

Shifting focus to words of affirmation, a study utilized fMRI to observe neural activities in couples during the act of giving and receiving verbal affirmations. The findings revealed that both expressing and receiving compliments activated brain regions associated with reward processing, such as the ventral striatum, and areas involved in social cognition, including the medial prefrontal cortex (Eckstein et al., 2023). These suggest that verbal affirmations not only provide pleasure but also enhance understanding and empathy between partners.

Research on self-affirmation has demonstrated activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Cascio et al., 2015), a region implicated in self-referential thinking and valuation, which is a key part of how we experience our sense of self. Furthermore, positive verbal interactions have been shown to improve brain function. Self-affirmation has been shown to lead to less anterior insula activity during subsequent stressful tasks, suggesting a potential mechanism for stress reduction (Dutcher et al., 2020).

Finally, quality time is verified to play a significant role in relationship satisfaction. A study from the Journal of Marriage and Family Therapy involving 1,367 low-income couples found that increased quality time, defined as the frequency and nature of shared activities reported by participants, significantly improved how couples manage stress and their ability to cope with challenges together (Carlson et al., 2021), Another study using diaries from 92 women measured quality time as the duration couples spent together engaging in shared activities showed that spending more time together on weekdays, especially when stress ws low, was linked to higher intimacy (Milek et al., 2015). These findings highlight the importance of quality time in building intimacy and reducing relationship stress, ultimately strengthening couples’ bonds.

(Photo: Getty Images)

While the Five Love Languages theory may lack scientific rigor, its principles are supported by various individual psychological and neurological findings. Thoughtfully considering and improving relationships through these frameworks can be beneficial to the parties involved. Each love language offers valuable insights into fostering interpersonal connection, though people rarely express affection through any single channel. Moreover, these expressions are not exclusive to romantic relationships—they can enhance friendships, family bonds, and even professional interactions.

The effectiveness of the Five Love Languages may be influenced by cognitive biases. For example, the Barnum effect leads individuals to accept vague, general statements as personally meaningful, causing them to perceive the Five Love Languages as uniquely tailored to their experiences with their romantic partners. Similarly, confirmation bias prompts people to focus on instances that align with their identified love language, reinforcing their belief in its accuracy.

Additionally, these frameworks have limitations. An overemphasis on gift-giving may encourage materialism, while acts of service or words of affirmation could potentially be misused for manipulation. Human connections are inherently complex, and relying too heavily on any single framework risks oversimplifying the nuanced dynamics of relationships.

Ultimately, the Five Love Languages framework - identifying physical touch, receiving gifts, acts of service, words of affirmation, and quality time as primary ways individuals express and receive love- can serve as a valuable tool for self-reflection and relationship development, but should not be treated as a universal solution. Genuine, healthy connections are built on open communication, mutual respect, and adaptability—elements that transcend any singular theory of human connection.

Works Cited

-

1. Light, K. C., Grewen, K. M., & Amico, J. A. (2005). More frequent partner hugs and higher oxytocin levels are linked to lower blood pressure and heart rate in premenopausal women. Biological Psychology, 69(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.002

-

2. Grewen, K. M., Anderson, B. J., Girdler, S. S., & Light, K. C. (2003). Warm Partner Contact Is Related to Lower Cardiovascular Reactivity. Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964280309596065

-

3. Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. The American Psychologist, 13(12), 673–685. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047884

-

4. Takano, T., & Mogi, K. (2019). Adult attachment style and lateral preferences in physical proximity. BioSystems, 181, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2019.05.002

-

5. Rim, S., Min, K. E., Liu, P. J., Chartrand, T. L., & Trope, Y. (2019). The Gift of Psychological Closeness: How Feasible Versus Desirable Gifts Reduce Psychological Distance to the Giver. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(3), 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218784899

-

6. Balconi, M., Fronda, G., & Vanutelli, M. E. (2019). A gift for gratitude and cooperative behavior: brain and cognitive effects. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 14(12), 1317–1327. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa003

-

7. Balconi, M., & Fronda, G. (2020). The “gift effect” on functional brain connectivity. Inter-brain synchronization when prosocial behavior is in action. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 5394–5394. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62421-0

-

8. Beck, L. A., & Clark, M. S. (2010). Looking a gift horse in the mouth as a defense against increasing intimacy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(4), 676–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.02.006

-

9. Eckstein, M., Stößel, G., Gerchen, M. F., Bilek, E., Kirsch, P., & Ditzen, B. (2023). Neural responses to instructed positive couple interaction: an fMRI study on compliment sharing. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsad005

-

10. Cascio, C. N., O’Donnell, M. B., Tinney, F. J., Lieberman, M. D., Taylor, S. E., Strecher, V. J., & Falk, E. B. (2016). Self-affirmation activates brain systems associated with self-related processing and reward and is reinforced by future orientation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(4), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsv136

-

11. Dutcher, J. M., Eisenberger, N. I., Woo, H., Klein, W. M. P., Harris, P. R., Levine, J. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2020). Neural mechanisms of self-affirmation’s stress buffering effects. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(10), 1086–1096. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa042

-

12. Carlson, R. G., Barden, S. M., Locklear, L., Dillman Taylor, D., & Carroll, N. (2022). Examining quality time as a mediator of dyadic change in a randomized controlled trial of relationship education for low‐income couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48(2), 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12554

-

13. Milek, A., Butler, E. A., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). The Interplay of Couple’s Shared Time, Women’s Intimacy, and Intradyadic Stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(6), 831–842. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000133