•

August 13, 2025

Technology has quietly woven itself into the fabric of our daily lives. We’ve let it into our pockets, strapped it to our wrists, and even accepted it into our bodies. Most of us have become accustomed to the daily monitoring and optimization that these technologies have made second nature. But what happens when devices shift their gaze toward our minds? Where do we draw the line against digital control?

With the rise of neurofeedback devices that demand the quantification, interpretation, and improvement of brain activity, we’re quickly hurtling toward a future where our own thoughts could be compromised. Under the guise of self-improvement, neurotechnology devices translate brain activity into data, subjecting the mind to innovative forms of control and raising urgent concerns. Does this technology truly reflect progress? Or will it only permit corporate control, surveillance, and new kinds of discrimination?

Figure 1. AI-generated illustration created with ChatGPT.

The allure of neurofeedback and its promises

Neurofeedback promises to “train our brains” by instructing individuals to modify brain behavior in a way that is “functionally advantageous” (Papo). This technology commonly utilizes electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures electrical activity in the brain through sensors on the scalp. While the promise of personal enhancement is enticing, therapeutic EEG technology is still in its early phases, with limitations such as being easily distorted by outside interference and the likelihood that many of the reported benefits are actually due to placebo effects (Loriette et al.; McCall and Wexler). Despite this, EEG neurofeedback tools are promoted as life-changing, reinforcing a culture of relentless self-optimization.

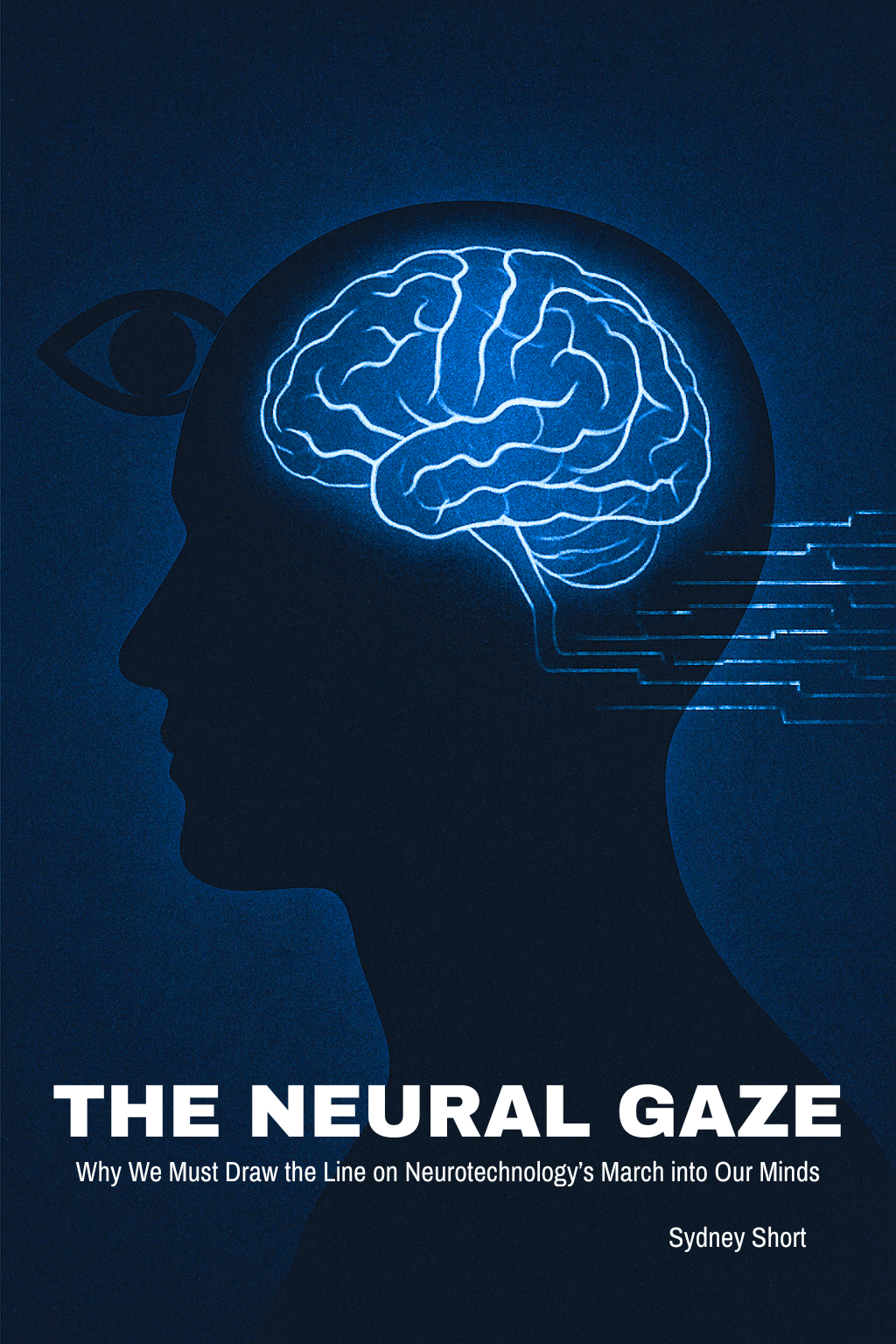

Companies including Neurosky, Emotiv, and Muse already market commercial neurodevices for improving sleep, meditation, and focus, appealing to consumers seeking to enhance brain function or health. In a society where nearly one in five Americans use a smart watch or fitness tracker (Blazina), it’s easy to see how neurofeedback may be the natural next step in self-optimization. However, as neurofeedback becomes more accessible and the pressures to optimize become increasingly inescapable, brain data is becoming a commercialized and normalized metric of health and performance. This encroachment closer and closer to the organ that controls our “humanness” forces us to question the once assumed right of brain autonomy. It also forces us to imagine the consequences of a world that privileges those with “better” brain metrics. How safe or how close are we from this reality?

Figure 2. EEG headsets from NeuroSky, Emotiv, and Muse. Composite created by Sydney Short using images from company websites.

The slippery slope from optimization to surveillance

If we continue blindly embracing tools that seek to revamp the human mind, it's not hard to envision how neurotechnology may reshape our workplaces and daily lives. For instance, imagine a society where everyone wears a device called a MindBand—a neural tracker that constantly monitors and records mental sharpness, focus, productivity levels, and emotional state. MindBands are mandatory at your workplace. While at your desk, you feel your thoughts wander. A flashing pop-up appears on your screen, “PLEASE RE-FOCUS!” You sigh and reluctantly force your attention back, aware of what each lapse could cost you. You worry your pay will be docked for daydreaming, while coworkers with better cognitive stats receive perks. The next day, you read your email only to find out that every employee’s brain data has been subpoenaed to investigate a massive investment fraud case. Even though you were not personally involved, you’ve secretly been discussing with a friend about matters that could easily get you fired. You hand over your MindBand to your boss, realizing you’ve grown dependent on it to even tell how you feel.

Figure 3. A simulated workplace alert with wearable neurotech headband in the foreground. Created by Sydney Short using icons and images provided by Canva and content generated with ChatGPT.

The hypothetical scenario of the MindBand may seem dystopian, but it mirrors many existing and emerging trends in neurotechnology. In fact, the integration of EEG-based monitoring systems has already begun in China where some train drivers and factory workers are reportedly required to wear EEG headsets that monitor fatigue and emotional state (Chan). Similarly, students in some Chinese classrooms have been fitted with EEG devices to encourage them to pay attention (McCall and Wexler). It’s only a matter of time before the surveillance use cases of neurofeedback are used in other parts of the world. As neurotechnology imposes new forms of authority and control, it’s clear that the brain is now on the forefront of a new kind of battlefield.

In today’s tech-driven society, every aspect of daily life and each and every move we make can be monitored and surveilled. It’s no secret that Meta, Amazon, Twitter, and other large tech companies take advantage of user data to cash in on targeted advertising through the use of privacy-invasive tracking technologies (“FTC Staff…”). Employees are just as vulnerable as their browsing history when it comes to surveillance in the workplace, where monitoring practices have evolved from simple productivity tracking to increasingly invasive forms of behavioral and biometric surveillance. From keylogging to tracking employees’ fitness through smart watches and sensors that monitor how many people are in a room, employers can easily gain access to what employees are doing and when they are doing it (“Business Booster…”; Harbert). Neurotechnology devices boost the reach of surveillance, offering new tools for companies to exploit.

Employers are already comfortable utilizing tracking software and devices, and are likely to enthusiastically embrace neurofeedback tools that promise company profits by supposedly boosting productivity and mental health (Min et al.; Wild). However, as metrics of “mental fitness” become performance benchmarks, new risks could emerge.

Neurotechnology’s hidden hierarchies

These neurodevices don’t simply measure brain activity, they define “good” cognitive performance. Focus, calm, and efficiency are all traits that this technology is built to reward. Whether it’s used for workplace surveillance, healthcare, or personal use, neurofeedback leads to non-neutral analyses of brain function, which may reinforce systemic bias and promote ableist or even eugenic ideas.

Social theorists like Michel Foucault have warned that when bodies are reduced to data points, they become sites of control. Neurofeedback reflects Foucault’s “clinical gaze,” which refers to when lived experiences are stripped away, leaving only numbers to be manipulated. Individuals are seen as brain metrics that can be monitored, adjusted, and improved according to normative standards. All technology is constructed within specific cultural contexts that define what is normal or valuable. Neurofeedback devices are no different as they embed neoliberal values of productivity and self-optimization into their very design.

Under the guise of self-improvement, individuals may begin to align their value as a person to their mental ability (Ajana). This is just like how you may feel disappointed in yourself if you fail to close all three rings on your Apple Watch, or if you exceed your allotted calories on your food tracking app. While these are issues in themselves, dangerous concerns arise when these measurements become the basis for how society functions.

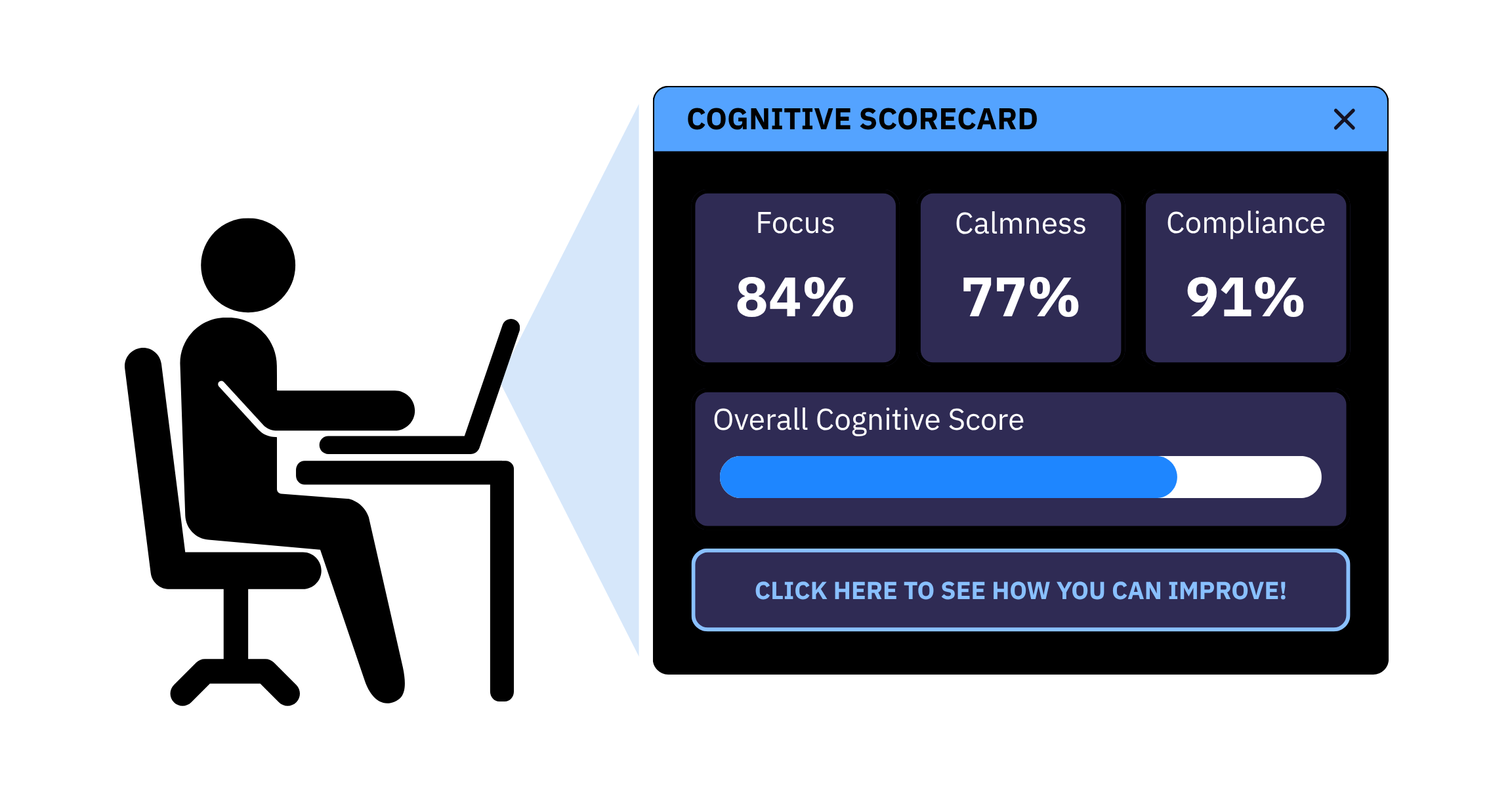

Figure 4. Cognitive scorecard illustration. Created by Sydney Short with icons provided by Canva.

Think back to the MindBand world where corporations gained access to sensitive brain data to exert control over employees. Now imagine if you were required to provide a “cognitive score” during the job application process. Individuals with cognitive impairments, neurological diseases, and psychiatric conditions could then be cast out from workplaces as technologies like the MindBand reinforce biopolitical hierarchies that dictate who is seen as cognitively “fit” enough to participate in society. Just because their brainwaves do not reflect what is deemed as normal, they are

In her book, Race After Technology, Ruha Benjamin describes that technology itself can act as a vessel for inequity, highlighting “social credit” programs that score and sort populations in ways that reproduce existing and inequitable social hierarchies. This describes how neurofeedback technologies risk embedding harmful social hierarchies by digitizing and categorizing mental performance. Implementing EEG-based technology as a “social credit” program creates a system that rewards individuals for giving up their privacy and sorts them based on cognitive measures. This logic turns brain data into a tool of biopolitical control, promoting a society where neural compliance becomes a condition for success. Individuals in a world with the forced universal adoption of devices such as MindBands may be subject to constant evaluation of their mental states and performance, fundamentally redefining what it means to be a “good worker” and even a “good citizen.” Those with mental health conditions or neurodivergence are automatically penalized and even excluded in such conditions, contributing to a society that favors “fit” individuals. These systems reinforce ableist standards that mistake compliance for competence.

Figure 5. Illustration by Valeria Petrone (2023), published in The Wire China.

This social restructuring describes a world where technology defines behavior, ranks it, and uses it as the basis for access to opportunity. Thus, neurofeedback encourages damaging mindsets and promotes inequality by creating hierarchies of individuals who are “cognitively fit,” those who can maintain unwavering focus at the office or supposedly have brainwave patterns mirroring high intelligence, and “cognitively inferior,” who may daydream at work, struggle with anxiety, or simply fail to produce the right neural waves on command. Ultimately, the fundamental ability of technology to dictate how society operates demonstrates how neurofeedback could facilitate a shift to a world that is once again plagued with eugenic logic. We now must decide the best course of action to protect ourselves from this inevitable evil.

What’s being done

Due to the extensive privacy concerns and the sensitive nature of neural data, a robust regulation framework is necessary to provide adequate safety measures regarding the development and deployment of neurotechnology devices. Senate Democratic leaders have expressed concerns to the FTC, urging neurotech companies to establish clear safeguards for the handling of neural data (Schumer et al.). For a recent article, Senator Chuck Schumer wrote an email to The Verge expressing, “Neural data is the most private, personal, and powerful information we have—and no company should be allowed to harvest it without transparency, ironclad consent, and strict guardrails. Yet companies are collecting it with vague policies and zero transparency (Del Valle).” While the USA does have a patchwork of states with some protection of brain data, it is clear our current legislation does not have the proper capacity to protect us from privacy or ethical dilemmas.

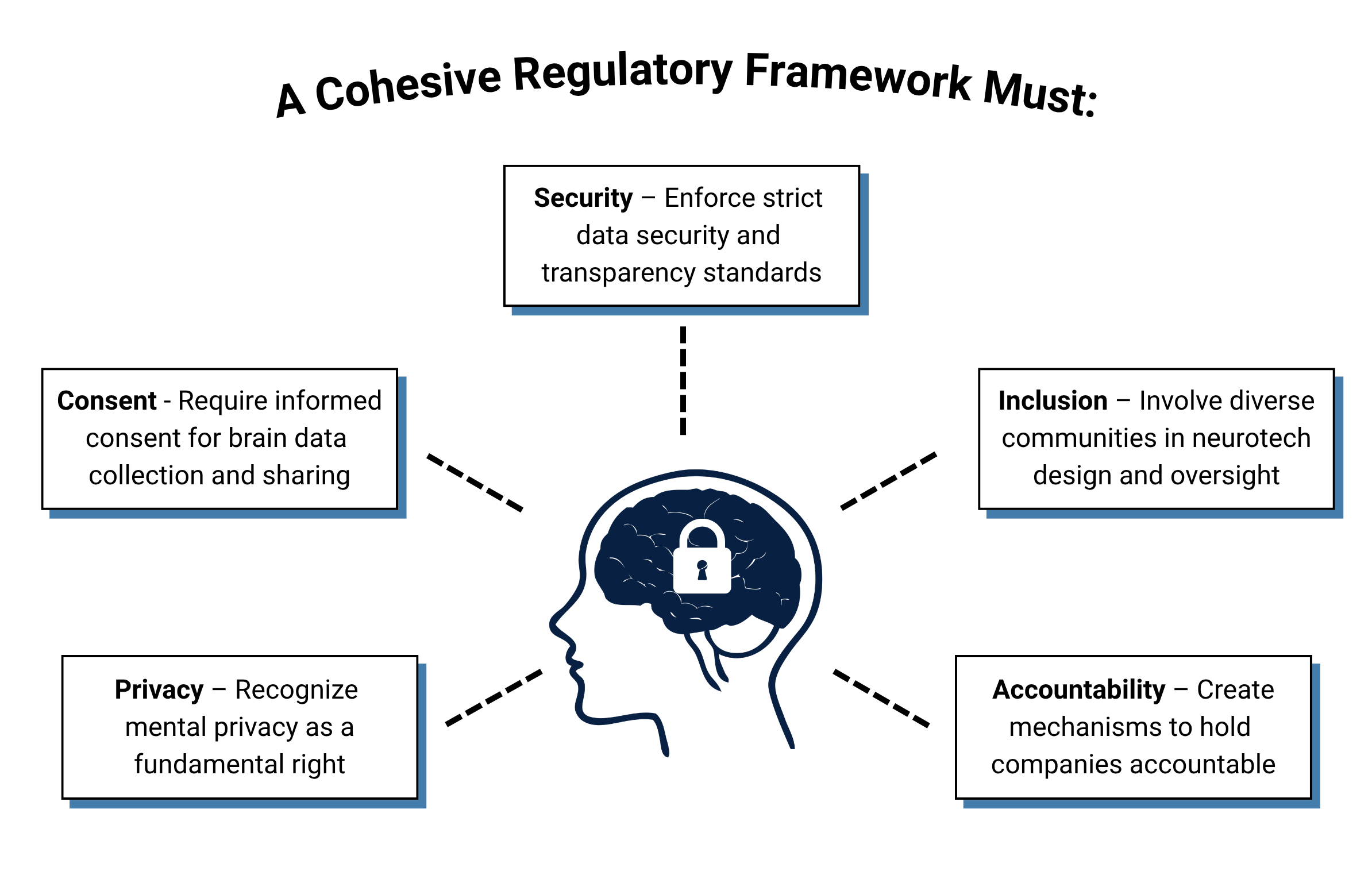

On an international level, agencies like the OECD and UNESCO have only recently begun outlining ethical frameworks for neurotechnology. UNESCO is currently developing a recommendation set for potential adoption in November of 2025, emphasizing the importance of respecting human rights, outlining shared values and principles, and proposing concrete policy actions to ensure the responsible development and use of neurotechnology (“Ethics of…”). If adopted, it will be capable of greatly influencing the development of national laws and practices on a global scale. Generally, a comprehensive regulatory framework must focus on the main aspects of neural rights, consent, security, inclusion, and accountability. It is also important to design a dynamic foundation, allowing for updates as technology evolves. Overall, we must continue fighting for protection, urging for concrete federal guidelines preventing neurotechnology companies from encroaching on our brains and protecting society from an inequitable future based on brain metrics and eugenics.

Figure 6. A cohesive regulatory framework for neurotechnology. Created by Sydney Short with icons provided by Canva.

Conclusions

While some may attribute the MindBand world to just another unhinged episode of Black Mirror and feel confident this is out of the realm of possibilities, we must be cautious and protect an inclusive and free-thinking society at all costs. Neurofeedback devices threaten to normalize invasive data practices, reinforce ableist hierarchies, and commodify cognition under the guise of self-optimization. If left unregulated, these technologies risk transforming mental function into a prerequisite for social participation, employment, and even self-worth. As Nita Farahany writes in her book, The Battle for Your Brain, “If people are willing to give up reams of personal data to keep in touch with their friends on Facebook, it seemed likely they would be willing to trade their brain privacy to swipe a screen or type with their minds.” We are so accustomed to giving up our privacy to utilize technology for our benefit that we may not realize our brains need protecting. By executing a comprehensive regulatory framework, we can ensure that neurotechnology serves the benefit of the human race. The brain must remain a sanctuary for thought, not a frontier for exploitation.

Works Cited

Ajana, Btihaj. “Digital Health and the Biopolitics of the Quantified Self.” Digital Health, vol. 3, Jan. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207616689509.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology. Polity Press, 2019.

Blazina, Carrie. “About One-in-five Americans Use a Smart Watch or Fitness Tracker.” Pew Research Center, 14 Apr. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/01/09/about-one-in-five-americans-use-a-smart-watch-or-fitness-tracker.

“Business Booster Or Big Brother: The Ins And Outs Of Employee Productivity Monitoring.” Schwab Gasparini Attorneys and Counselors, Mar. 2024, www.schwabgasparini.com/blog/employee-productivity-monitoring.

Chan, Tara. “These Chinese workers’ brain waves are being monitored.” World Economic Forum, May 2018, www.weforum.org/stories/2018/05/china-is-monitoring-employees-brain-waves-and-emotions-and-the-technology-boosted-one-companys-profits-by-315-million.

ChooseMuse. (n.d.). Muse 2. Muse. https://choosemuse.com/products/muse-2

Del Valle, Gaby. “Neurotech Companies Are Selling Your Brain Data, Senators Warn.” The Verge, 28 Apr. 2025, www.theverge.com/policy/657202/ftc-letter-senators-neurotech-companies-brain-computer-interface.

“Draft Text of the Recommendation on the Ethics of Neurotechnology.” UNESCO, 2025, unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000393395.

Emotiv. (n.d.). Epoc X. Emotiv. https://www.emotiv.com/products/epoc-x?srsltid=AfmBOopYl8yvp2iSVbEG2mtUeJlKaTYi3zrHY1RLdpbQM2slB9Q7Blso

“Ethics of neurotechnology.” UNESCO, www.unesco.org/en/ethics-neurotech/recommendation#:~:text=This%20special%20mandate%2C%20entrusted%20by,UNESCO.

Farahany, Nita A. The Battle for Your Brain. St. Martin’s Press, 2023.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic. Tavistock, 1973.

“FTC Staff Report Finds Large Social Media and Video Streaming Companies Have Engaged in Vast Surveillance of Users With Lax Privacy Controls and Inadequate Safeguards for Kids and Teens.” Federal Trade Commission, 25 Sept. 2024, www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/09/ftc-staff-report-finds-large-social-media-video-streaming-companies-have-engaged-vast-surveillance.

Harbert, Tam. “Watching the Workers.” SHRM, 21 Dec. 2023, www.shrm.org/topics-tools/news/all-things-work/watching-workers.

Loriette, C., et al. “Neurofeedback for cognitive enhancement and intervention and brain plasticity.” Revue Neurologique, vol. 177, no. 9, Nov. 2021, pp. 1133–44. doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2021.08.004.

McCall, Iris Coates, and Anna Wexler. “Chapter One - Peering into the mind? The ethics of consumer neuromonitoring devices.” Developments in Neuroethics and Bioethics, vol. 3, 2019, pp. 1–22. doi.org/10.1016/bs.dnb.2020.03.001.

Min, Beomjun, et al. “The Effectiveness of a Neurofeedback-Assisted Mindfulness Training Program Using a Mobile App on Stress Reduction in Employees: Randomized Controlled Trial.” JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth, vol. 11, Aug. 2023, p. e42851. https://doi.org/10.2196/42851.

NeuroSky. (n.d.). MindWave. NeuroSky. https://store.neurosky.com/pages/mindwave

Papo, David. “Neurofeedback: Principles, Appraisal, and Outstanding Issues.” European Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 49, no. 11, Dec. 2018, pp. 1454–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14312.

Petrone, V. (2023). Illustration for “The grand experiment: Social credit in China.” The Wire China. https://www.thewirechina.com/2023/12/17/the-grand-experiment-social-credit-china/

Schumer, Charles E., et al. Letter to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission Regarding the Handling of Sensitive Neural Data. 28 Apr. 2025, www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Neural%20Data%20Letter%20-%2004.28.2025-%20updated.pdf.

Wild, Jane. “Wearables in the Workplace and the Dangers of Staff Surveillance.” Financial Times, 12 Feb. 2024, www.ft.com/content/089c0d00-d739-11e6-944b-e7eb37a6aa8e.