•

October 10, 2024

.jpeg?alt=media&token=d0e8913a-783c-472d-9a3e-da879fc337a7)

The Human Experience

As the sun dips below a glossy horizon, its meaning carries more weight than a mere visual spectacle. For one, it’s a passionate blaze sequestered within the vacuum of space. For another, it’s a religious deity curtailing its daily reign. For me, it’s a symbol of life, acting as a blanket of emotional warmth, memories, and vivid sensations. This idea of qualia, a subjective, ineffable experience shaping our perception, draws into question the idea of Human Subjectivity.

From ethics to politics, to interpersonal relationships, Human Subjectivity sits at the forefront of human conflict. While it is useful to try and understand these problems from a domain-specific viewpoint, it is equally, if not more crucial, to study the players responsible for constructing these varied perceptions. To do so, and understand the social implications of these clashing interpretations, we must answer a core question: How does the way people see the world differ between individuals, and how does human perception lack objectivity in the first place?

It takes as little as a box of crayons to see that children have rich, abstract imaginations. Yet to be encumbered by cultural parameters and lacking particular foresight established through neurological development, their thoughts run freely through a landscape of ordered chaos. With the hindsight of maturity we can recognize these constructed worlds to be false; however, what renders them false to the child? While the outcome of this perceptual dialogue remains unspoken, it does raise an interesting question; what is a correct perspective and how does it come about?

To answer this question, let’s focus on three schools of thought, beginning with perceptual comprehension, moving to the cultural environment, and ending with expertise.

Perceptual Comprehension

First, let's begin with the aforementioned gap in perceptual comprehension between children and adults. Imagine a living room with a parent, Sara, and her child, Jay. While Sara picks up a magazine to read, Jay sees a collection of colorful photos that overpower ordered symbols. While Sara sees a cloth draped over a table, Jay sees a wizard cape concealing an irregularly shaped man. For Jay, his interpretation stands to be true, and amongst his peers, this seemingly fictitious narrative is sometimes confirmed. Conversely, Sara, as do many of us, believes otherwise, as our developed cognitive faculties provide us with a more tangible, interactable existence.

Although Jay’s account of reality seems misguided, it does teach us a valuable lesson. Specifically, the idea that our perception is malleable, formed through fluctuating variables like neurological development, for example.

Cultural Environment

This susceptibility of perception becomes more apparent within the second school of thought, cultural upbringing. A digestible example of a cultural upbringing’s influence on perception comes from the realm of linguistics, specifically its expression of color.

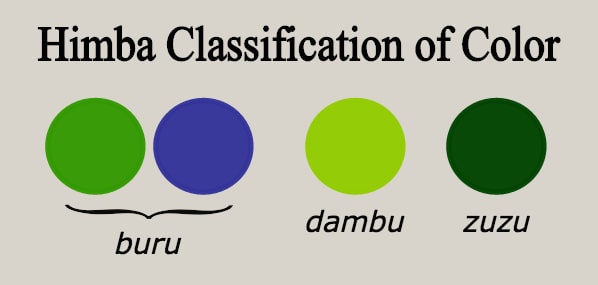

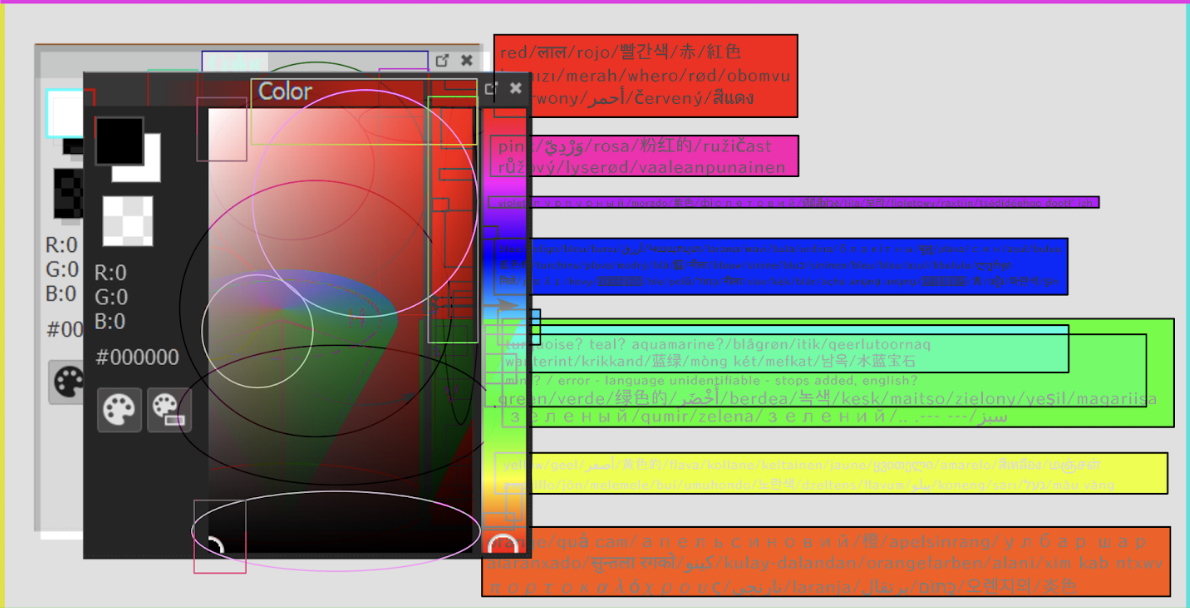

Color exists as a large spectrum of melding colors. However, through language, we establish arbitrary boundaries, creating culturally dependent distinctions within an objective spectrum. These borders allow us to better navigate the abstract concept of color, discussing and interacting with color whilst using more comprehensible tools. It’s essential to understand these linguistic “trailheads” exist purely as social constructs and are used as a cultural framing tool to influence the way humans perceive color.

An example of this comes from a study on color categories, which provides evidence in support of the previously discussed cultural relativity hypothesis. This series of experiments conducted by the Department of Psychology, University of Essex studied the color perception of the Himba tribe, comparing aspects of their relationship with color to that of the English and Berinmo languages.

The findings of the study explored the varying implications of differences in linguistic labeling with color dependent memory abilities, boundary shifts, and color naming tendencies all fluctuating between languages. In short, it discovered that there were differences in how Himba tribe members perceived color relative to Western labeling. Why was this?

Though colors remain objective, the environment of the Himba tribe has fostered cultural parameters that influence how they see color. Their ability to identify differences between particular colors contrasts from a Westernized perspective where their “trailheads” are placed differently amongst the color spectrum. These distinctions further highlight the relationship between cultural parameters and individual perception.

This idea of linguistic relativism is not restricted to color; we see its impact through the way speakers of gendered languages interpret objects associated with gender. When asked to describe particular inanimate objects, native speakers of languages will often subconsciously attach gendered cultural attributes to the object, perceiving those objects through the relevant gender lens.

Let’s look at the word for “bed” in Italian versus Spanish. If asked about their beds, an Italian speaker may describe stereotypical masculine attributes, such as a brooding frame, sturdy metal, and inserted brackets, while a Spanish speaker might explain its stereotypical feminine aspects, such as a comfortable mattress, a particular sheet, and feather pillows. The way the bed is constructed in their minds typically goes through a gendered framework, attaching arbitrary, socially constructed characteristics to inanimate objects. This not only perpetuates said beliefs within social groups but additionally fuels the established pretext which serves as the foundation for this cultural belief system.

Through these examples we can understand how despite not being the sole determiner of perception, language does influence the way we see and think about the world, best expressed through the idea of linguistic relativism.

Expertise

The last school of thought is built around the idea of practice, or, more specifically, individual expertise. Expertise can best be defined as the fluctuation between the perception of a behavior and the practice of that behavior over an extended period of time. A prime example of this comes from professional sports, such as the NFL.

When an average person is watching a football game, they watch it with its basic rules in mind, perhaps catching a flashy move or two. When a pro watches the field, they visualize the routes made by each player, predicting what will happen next. For them, they literally view the game differently, subconsciously utilizing their practiced understanding to see the game in a new light. The football game never changed, its actions and behaviors remain constant, rather a shifting knowledge of the game results in the same input being interpreted in a new manner.

While football is a good example of understanding this concept, it can more broadly be applied to the idea of practice in general. Through practice, experts of all crafts can see domain-specific problems differently, relaying their current input over past experiences. This learned ability stresses the old quote, “practice makes perfect” as it is the practice of a particular action that allows an individual to differently perceive specific problems.

These three variables demonstrate how reality is perceived differently between individuals. Even though the world exists in an objective sense, our neurological differences, cultural upbringing, and practiced abilities contribute to how we see the world.

This deconstructs the myth of human objectivity, highlighting how our interpretations of the world may be best described as a mass amalgamation of varying subjective experiences. Here lies the issue of Human Subjectivity and Experience: we know the world to be of our subjective experience, therefore we must be aware of this shortcoming in our perception whilst acknowledging the implications of playing into a homogenous narrative.

.jpeg?alt=media&token=fe2f1a51-abfb-46a0-9759-cd99175007e5) Part 1

Part 1

.jpg?alt=media&token=ecbcd0dc-27bf-4599-99e3-b6fe0c230848) Part 2

Part 2

.jpg?alt=media&token=363fbbc2-3db9-48cb-9613-dbac09bd2f34) Part 3

Part 3